GFS Paper

Here is my understanding about Google File System from reading the GFS paper. Some other references: MIT’s lecture video. I will use mostly text here- some of it is directly copied from the paper. So if you need a video walkthrough of the paper with diagrams, etc, here is a good youtube video.

This paper was published in 2003, and while the concepts used were not new to academia, GFS put those to use in production. So in that sense it was revolutionary. Why did I read it now? Well, DeepSeek’s 3FS was recently announced/ open sourced and I wanted to read it but not much material seems available yet (Some reference is there as a part of an old paper… maybe I will read that next). But maybe that was a trigger.

The ideas relevant in this description include: distributed applications, serialization, heartbeat pings, consistency, hierarchical file system, write-ahead-log, etc.

GFS was designed with specific goals/ usage patterns for Google’s applications. For example, random access is not a stated goal, files are large, mostly blocks are appended than overwritten, etc. The paper mentions documents- something like web-crawler result files. But maybe while reading the paper, it’d help to think of large files- like GB sized youtube videos- being chunked apart and pieced back together.

Client applications access GFS using a library. This library provides an API and some utilities. When the word ‘client’ is used in the rest of this post, think of it as this client library.

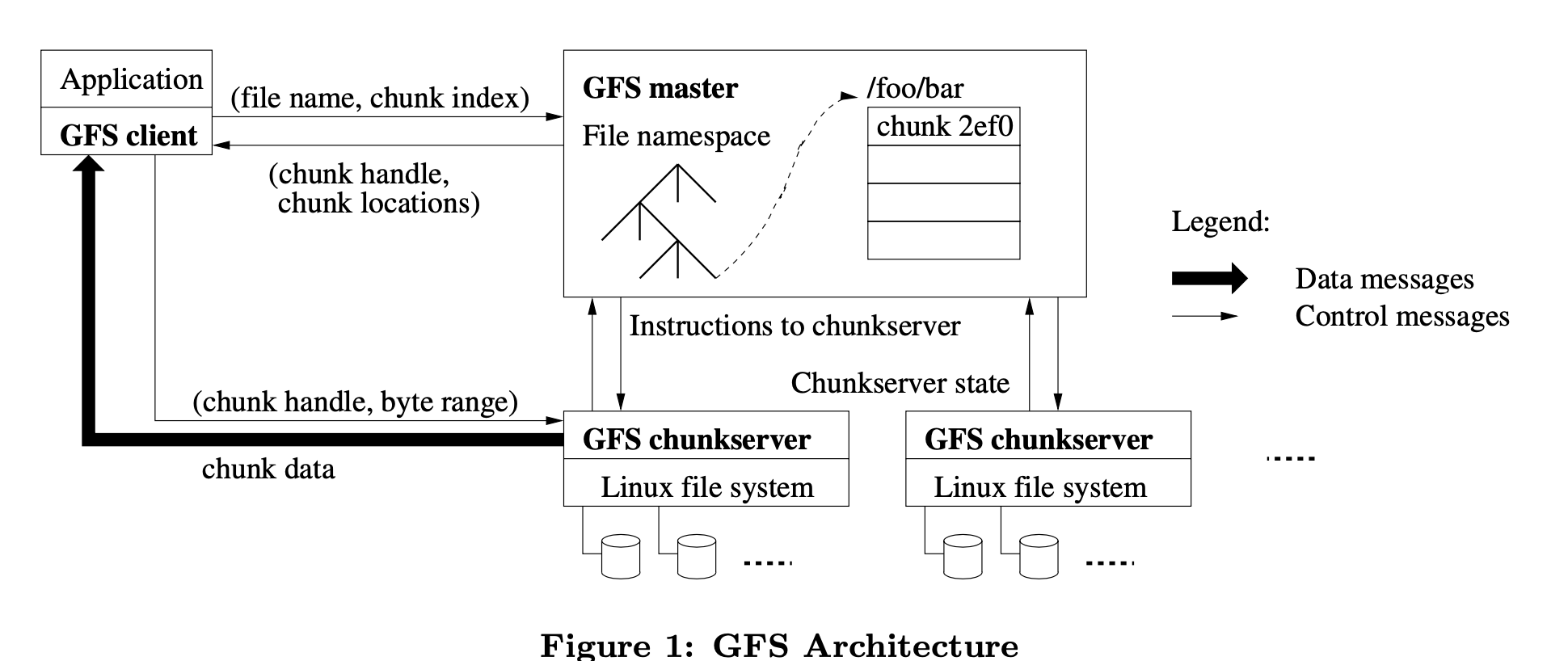

A GFS cluster consists of a single master and multiple chunk-servers and is accessed by multiple clients. They use commodity hardware.

GFS stores large files by splitting them into fixed sized chunks of 64MB each. Each chunk is stored as a separate file in linux local disk. The machines storing these chunks are called chunk servers. Chunks of a file may be stored on different chunk servers. Chunks are replicated and replicas are stored on different servers. (The paper talks about racks, etc. but not much about data centers. Maybe they were using a single data center then.)

The workloads primarily consist of two kinds of reads: large streaming reads and small random reads. The workloads also have many large, sequential writes that append data to files.

In applications using GFS, files are often used as producer-consumer queues or for many-way merging. Hundreds of producers, running one per machine, concurrently append to a file. Atomicity with minimal synchronization overhead is essential.

High sustained bandwidth is more important than low latency.

Each chunk is identified by an immutable and globally unique 64 bit chunk handle assigned by the master at the time of chunk creation. Chunkservers read or write chunk data specified by a chunk handle and byte range. Large chunk size reduces metadata stored on the master and also reduces client-master interaction for this metadata. Clients can also keep TCP connection to chunk server alive for longer duration as they need to talk to fewer chunk servers due to bigger chunk sizes.

The master maintains all file system metadata. This includes the namespace, access control information, the mapping from files to chunks, and the current locations of chunks. It also controls system-wide activities such as chunk lease management, garbage collection of orphaned chunks, and chunk migration between chunkservers. The master periodically communicates with each chunkserver in HeartBeat messages to give it instructions and collect its state.

Clients interact with the master for metadata operations, but all data-bearing communication goes directly to the chunkservers. Clients never read and write file data through the master. Instead, a client asks the master which chunkservers it should contact. The client then caches this information for a limited time and interacts with the chunkservers directly for many subsequent operations.

First, using the fixed chunk size, the client translates the file name and byte offset specified by the application into a chunk index within the file. Then, it sends the master a request containing the file name and chunk index. The master replies with the corresponding chunk handle and locations of the replicas. The client caches this information using the file name and chunk index as the key.

The client then sends a request to one of the replicas, most likely the closest one. The request specifies the chunk handle and a byte range within that chunk. Further reads of the same chunk require no more client-master interaction until the cached information expires or the file is reopened. In fact, the client typically asks for multiple chunks in the same request and the master can also include the information for chunks immediately following those requested. This extra information sidesteps several future client-master interactions at practically no extra cost.

The Master and metadata

The master stores three major types of metadata: the file and chunk namespaces, the mapping from files to chunks, and the locations of each chunk’s replicas. All metadata is kept in the master’s memory. The first two types (namespaces and file-to-chunk mapping) are also kept persistent by logging mutations to a write-ahead-log stored on the master’s local disk and replicated on remote machines. This helps when master fails and in-memory data is lost. Based on the write-ahead-log (in the paper they call it operations log), the files and chunks, as well as their versions, are all uniquely and eternally identified by the logical times at which they were created. The write-ahead-log being critical persistence record is replicated on multiple remote machines and the master responds to a client operation only after flushing the corresponding log record to disk both locally and remotely (flushed in batches; not real time). To minimize startup time, they keep the log small. The master checkpoints its state whenever the log grows beyond a certain size so that it can recover by loading the latest checkpoint from local disk and replaying only the limited number of log records after that. The checkpoint is in a compact B-tree like form that can be directly mapped into memory and used for namespace lookup without extra parsing. The master switches to a new log file and creates the new checkpoint in a separate thread. The new checkpoint includes all mutations before the switch. It can be created in a minute or so for a cluster with a few million files. When completed, it is written to disk both locally and remotely. Recovery needs only the latest complete checkpoint and subsequent log files. Older checkpoints and log files can be freely deleted, though they keep a few around to guard against catastrophes. A failure during checkpointing does not affect correctness because the recovery code detects and skips incomplete checkpoints. This persistence mechanism reminded me of SSTables and memtable.

The master does not store chunk location information persistently. Instead, it asks each chunkserver about its chunks at master startup and whenever a chunkserver joins the cluster.

GFS Consistency Model

I think this section would be easier to understand if you watch MIT’s video linked above and the leases and mutation order section below.

A mutation is an operation that changes the contents or metadata of a chunk such as a write or an append operation. When a mutation succeeds without interference from concurrent writers, the affected region is defined (and by implication consistent): all clients will always see what the mutation has written. Concurrent successful mutations leave the region undefined but consistent: all clients see the same data, but it may not reflect what any one mutation has written. Typically, it consists of mingled fragments from multiple mutations. A failed mutation makes the region inconsistent (hence also undefined): different clients may see different data at different times.

Data mutations may be writes or record appends. A write (in infrequent cases, it could be an overwrite as well) causes data to be written at an application-specified file offset. A “regular” append is merely a write at an offset that the client believes to be the current end of file. Whereas a record append causes data (the “record”) to be appended atomically at least once even in the presence of concurrent mutations, but at an offset of GFS’s choosing. The offset is returned to the client and marks the beginning of a defined region that contains the record. In addition, GFS may insert padding or record duplicates in between. They occupy regions considered to be inconsistent and are typically dwarfed by the amount of user data.

After a sequence of successful mutations, the mutated file region is guaranteed to be defined and contain the data written by the last mutation. GFS achieves this by (a) applying mutations to a chunk in the same order on all its replicas, and (b) using chunk version numbers to detect any replica that has become stale because it has missed mutations while its chunkserver was down. Afterwards, these stale replicas are never involved in another mutation or given to clients asking the master for chunk locations. They are garbage collected at the earliest opportunity.

Readers deal with the occasional padding and duplicates as follows. Each record prepared by the writer contains extra information like checksums so that its validity can be verified. A reader can identify and discard extra padding and record fragments using the checksums. If it cannot tolerate the occasional duplicates (e.g. if they would trigger non-idempotent operations), it can filter them out using unique identifiers in the records.

Leases and Mutation Order

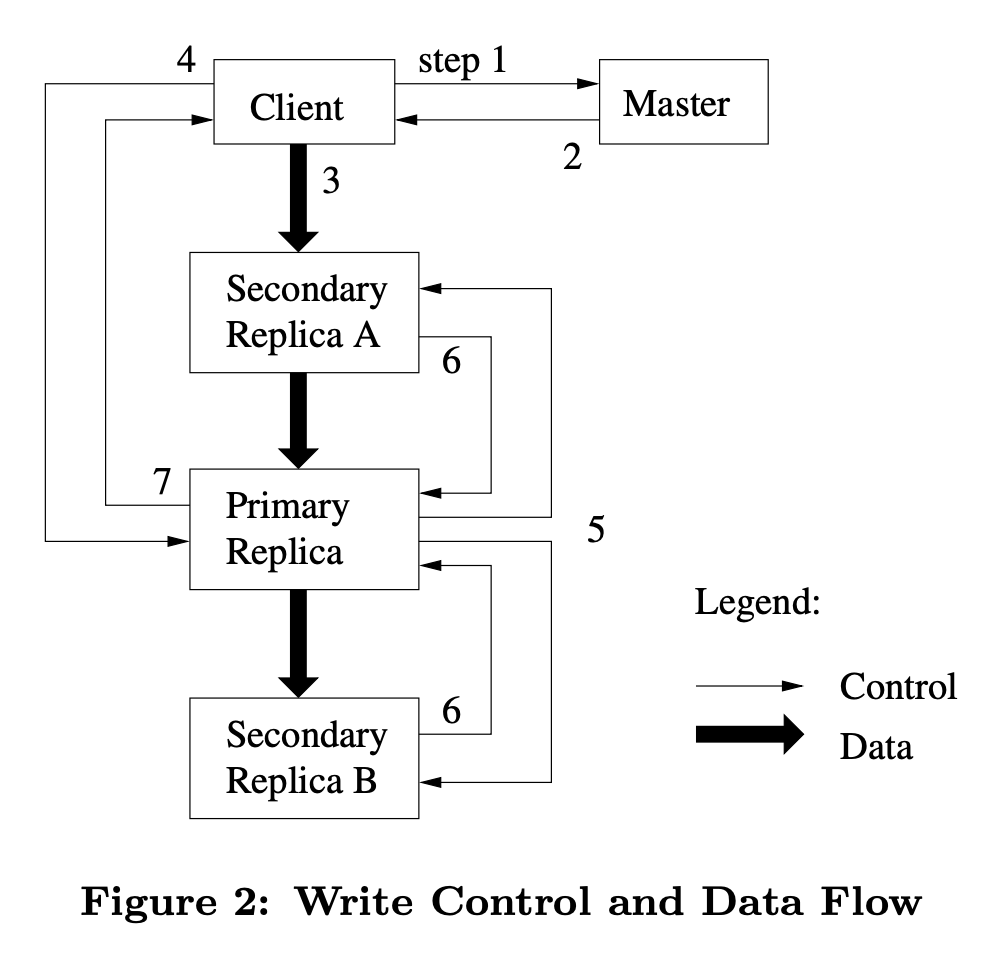

Each mutation is performed at all the chunk’s replicas. GFS uses leases to maintain a consistent mutation order across replicas. The master grants a chunk lease to one of the replicas, which is called the primary. The primary picks a serial order for all mutations to the chunk. All replicas follow this order when applying mutations. Thus, the global mutation order is defined first by the lease grant order chosen by the master, and within a lease by the serial numbers assigned by the primary.

- The client asks the master which chunkserver holds the current lease for the chunk and the locations of the other replicas. If no one has a lease, the master grants one to a replica it chooses (not shown in the above diagram).

- The master replies with the identity of the primary and the locations of the other (secondary) replicas. The client caches this data for future mutations. It needs to contact the master again only when the primary becomes unreachable or replies that it no longer holds a lease.

- The client pushes the data to all the replicas. A client can do so in any order. Each chunkserver will store the data in an internal LRU buffer cache until the data is used or aged out. By decoupling the data flow from the control flow, we can improve performance by scheduling the expensive data flow based on the network topology regardless of which chunkserver is the primary.

- Once all the replicas have acknowledged receiving the data, the client sends a write request to the primary. The request identifies the data pushed earlier to all of the replicas. The primary assigns consecutive serial numbers to all the mutations it receives, possibly from multiple clients, which provides the necessary serialization. It applies the mutation to its own local state in serial number order.

- The primary forwards the write request to all secondary replicas. Each secondary replica applies mutations in the same serial number order assigned by the primary.

- The secondaries all reply to the primary indicating that they have completed the operation.

- The primary replies to the client. Any errors encountered at any of the replicas are reported to the client. In case of errors, the write may have succeeded at the primary and an arbitrary subset of the secondary replicas. (If it had failed at the primary, it would not have been assigned a serial number and forwarded.) The client request is considered to have failed, and the modified region is left in an inconsistent state. The client library code handles such errors by retrying the failed mutation. It will make a few attempts at steps (3) through (7) before falling back to a retry from the beginning of the write.

If a write by the application is large or straddles a chunk boundary, GFS client code breaks it down into multiple write operations.

While control flows from the client to the primary and then to all secondaries, data is pushed linearly along a carefully picked chain of chunkservers in a pipelined fashion.

Atomic Record Appends

(Again MIT video may help.) GFS provides an atomic append operation called record append. In a traditional write, the client specifies the offset at which data is to be written. Concurrent writes to the same region are not serializable: the region may end up containing data fragments from multiple clients. In a record append, however, the client specifies only the data. GFS appends it to the file at least once atomically (i.e., as one continuous sequence of bytes) at an offset of GFS’s choosing and returns that offset to the client.

Record append is a kind of mutation and follows the control flow in the diagram above with only a little extra logic at the primary. The client pushes the data to all replicas of the last chunk of the file. Then, it sends its request to the primary. The primary checks to see if appending the record to the current chunk would cause the chunk to exceed the maximum size (64 MB). If so, it pads the chunk to the maximum size, tells secondaries to do the same, and replies to the client indicating that the operation should be retried on the next chunk. (Record append is restricted to be at most one-fourth of the maximum chunk size to keep worst-case fragmentation at an acceptable level.) If the record fits within the maximum size, which is the common case, the primary appends the data to its replica, tells the secondaries to write the data at the exact offset where it has, and finally replies success to the client.

If a record append fails at any replica, the client retries the operation. As a result, replicas of the same chunk may contain different data possibly including duplicates of the same record in whole or in part. GFS does not guarantee that all replicas are bytewise identical. It only guarantees that the data is written at least once as an atomic unit. This property follows readily from the simple observation that for the operation to report success, the data must have been written at the same offset on all replicas of some chunk. Furthermore, after this, all replicas are at least as long as the end of record and therefore any future record will be assigned a higher offset or a different chunk even if a different replica later becomes the primary.

Snapshot

When the master receives a snapshot request, it first revokes any outstanding leases on the chunks in the files it is about to snapshot. This ensures that any subsequent writes to these chunks will require an interaction with the master to find the lease holder. This will give the master an opportunity to create a new copy of the chunk first. After the leases have been revoked or have expired, the master logs the operation to disk. It then applies this log record to its in-memory state by duplicating the metadata for the source file or directory tree. The newly created snapshot files point to the same chunks as the source files. The first time a client wants to write to a chunk C after the snapshot operation, it sends a request to the master to find the current lease holder. The master notices that the reference count for chunk C is greater than one. It defers replying to the client request and instead picks a new chunk handle C’. It then asks each chunkserver that has a current replica of C to create a new chunk called C’. By creating the new chunk on the same chunkservers as the original, the data can be copied locally, not over the network.

Master Operation

The master executes all namespace operations. In addition, it manages chunk replicas throughout the system: it makes placement decisions, creates new chunks and hence replicas, and coordinates various system-wide activities to keep chunks fully replicated, to balance load across all the chunkservers, and to reclaim unused storage.

GFS logically represents its namespace as a lookup table mapping full pathnames to metadata. With prefix compression, this table can be efficiently represented in memory. Each node in the namespace tree (either an absolute file name or an absolute directory name) has an associated read-write lock. One nice property of this locking scheme is that it allows concurrent mutations in the same directory. For example, multiple file creations can be executed concurrently in the same directory: each acquires a read lock on the directory name and a write lock on the file name. The read lock on the directory name suffices to prevent the directory from being deleted, renamed, or snapshotted. The write locks on file names serialize attempts to create a file with the same name twice.

Replicas: Creation, Re-replication, Rebalancing

Chunk replicas are created for three reasons: chunk creation, re-replication, and rebalancing. When the master creates a chunk, it chooses where to place the initially empty replicas. It considers several factors. (1) Place new replicas on chunkservers with below-average disk space utilization. Over time this will equalize disk utilization across chunkservers. (2) Limit the number of “recent” creations on each chunkserver. Although creation itself is cheap, it reliably predicts imminent heavy write traffic because chunks are created when demanded by writes, and in append-once-read-many workload they typically become practically read-only once they have been completely written. (3) Spread replicas of a chunk across racks.

The master re-replicates a chunk as soon as the number of available replicas falls below a user-specified goal.

The master re-balances replicas periodically: it examines the current replica distribution and moves replicas for better disk space and load balancing.

Master Replication

If its machine or disk fails, monitoring infrastructure outside GFS starts a new master process elsewhere with the replicated write-ahead-log. Clients use only the canonical name of the master (e.g. gfs-test), which is a DNS alias that can be changed if the master is relocated to another machine. Moreover, “shadow” masters provide read-only access to the file system even when the primary master is down. They are shadows, not mirrors, in that they may lag the primary slightly, typically fractions of a second.

Data Integrity

Each chunkserver uses checksum to detect corruption of stored data.

A 64MB chunk is broken up into 64KB blocks. Each has a corresponding 32 bit checksum. Like other metadata, checksums are kept in chunkserver’s memory and also stored persistently with logging, separate from user data.

For reads, the chunkserver verifies the checksum of data blocks that overlap the read range before returning any data to the requester, whether a client or another chunkserver. Therefore chunkservers will not propagate corruptions to other machines. If a block does not match the recorded checksum, the chunkserver returns an error to the requestor and reports the mismatch to the master. In response, the requestor will read from other replicas, while the master will clone the chunk from another replica. After a valid new replica is in place, the master instructs the chunkserver that reported the mismatch to delete its replica.

GFS client code further reduces this overhead by trying to align reads at checksum block boundaries. Moreover, checksum lookups and comparison on the chunkserver are done without any I/O, and checksum calculation can often be overlapped with I/Os. (The optimization mentioned in the last part- overlapped with I/O- makes me sad for not getting a CS degree. How many such fine things must be going wasted on me just because I am not aware enough!)

Some passing observations

When you are learning about distributed systems, this is one of the first papers/ systems you learn about. Not many advanced concepts are used (transactions, multi-master, paxos, for example), some trade-off are made (like on consistency). And yet a great system was designed (the paper shares some metrics of actual GFS clusters being used). In that sense it was a very simple paper. Probably, of all the tech-papers I read so far, I finished reading this the fastest. My basic familiarity with some of the concepts (thanks to having read some other papers, Designing Data Intensive Applications book, etc.) must have helped.

In all distributed systems, failures are far too common. You probably even remember that Leslie Lamport’s quote or maybe Joe Armstrong view of the world. But from the papers which I have read/ documented on this site, only Google’s BigTable paper talked about error scenarios/ worst cases enough. Of course, all these systems, do handles failure, etc. But the papers did not talk a lot about those. Ever since reading Michael Nygard’s book ‘Release It’, that is the first thing I think about when looking at a system- how does it handle failure, is it a recovery-oriented design, etc.